(Co-written by Monique Judge, originally published on Medium.)

It all started with a ruined Wednesday morning.

A tweet of mine had found its way into a Washington Post op-ed calling for the dismissal of University of Missouri professors accused of assaulting students at a rally celebrating the resignation of the school president. Normally, this wouldn’t bother me; I’d grown accustomed to journalists using my tweets in their stories without giving me so much as a heads up (which usually leaves me open to trolling), and my Twitter account has never been private. But, as I’d spent the last 48 hours ridding my mentions of trolls wanting to debate First Amendment rights and freedom of the press, I was in no mood to entertain any more, and there was something about this particular post that stunk.

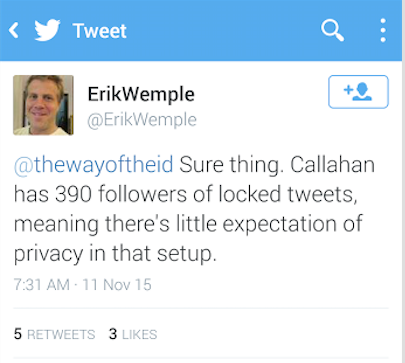

When WaPo blogger Erik Wemple couldn’t get in contact with one of the professors he decided to publicly shame, he used a source that provided him with a screenshot of that professor’s locked Twitter account. They were a handful of fairly innocuous retweets from myself and several other black writers commenting on the press’s inability to handle the Mizzou protesters with care. (More on the rather interesting optics of this later.) We don’t know who the source is, because Wemple is protecting them. We don’t see any actual tweets from the professor himself to put those retweets into context. When I reached out to Wemple, he claimed the retweets provided insight into the professor’s thoughts. And when I asked about the use of the screencaps, Wemple responded:

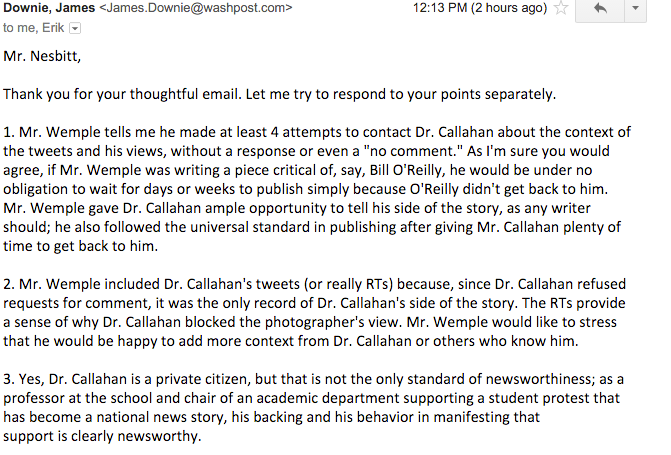

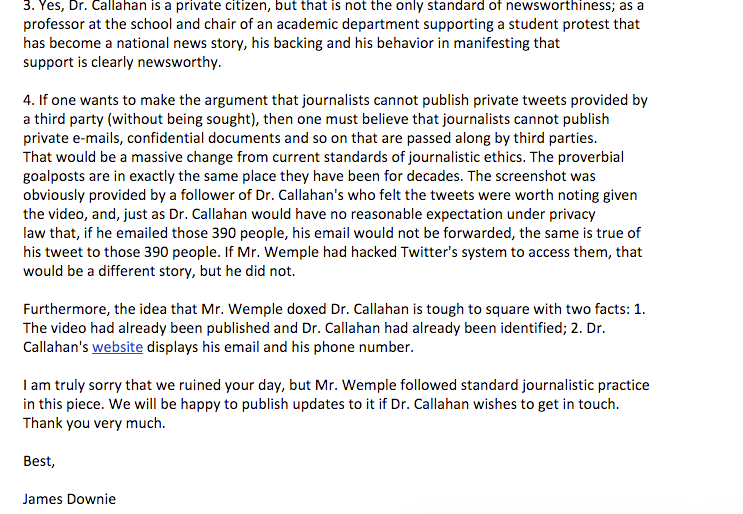

So, I sent a letter raising my concerns to Wemple’s editor, James Downie. This was his response:

(To Downie’s credit, he apologized for misgendering me on Twitter.)

According to Wemple and Downie, the professor’s 390 Twitter followers negated any expectation of privacy he may have had. Since the professor didn’t make himself available to be interviewed, Wemple was well within his rights as a reporter to use the screencaps of the professor’s private account the source had provided as a statement, of sorts. I’m not sure what the reader was supposed to glean from this, other than the professor’s proficiency at using the “Retweet” button. In any case, it has left the professor open to another wave of trolls and undesirables ready to harass him and call for his head.

Twitter — and the tweets of private citizens being public domain — has long been a point of contention. While Hamilton Nolan’s snide declaration in Gawker last year may have served as the definitive answer for many working journalists, it might have also contributed to the rapid erosion of public trust. But there’s something about Nolan’s post that’s worth noting:

“If you do not want your Twitter to be public, you can make it private. Then it will not be public. If you do not make it private, it will be public.”

The professor did, in fact, make his account private. He did not intend for anyone beyond his 390 followers to see those tweets. He had, in fact, an expectation of privacy, which was violated by Erik Wemple and the Washington Post.

This isn’t the first time a journalist or a blogger has exercised questionable judgment in pursuit of pageviews. Last week, American Conservative blogger Rod Dreher published the locked tweets of a theologian he was briefly obsessed with taking down. (I won’t link to the exact post out of privacy for her, but it remains up for the world to see.) It is unclear whether Dreher followed her on Twitter himself, or if he, like Wemple, had an eager source willing to do his dirty work.

Makerbase Co-Founder and CEO Anil Dash highlights the problem with treating the tweets of private citizens like those of public figures in his Medium essay, “What Is Public?” An excerpt:

“It has so quickly become acceptable practice within mainstream web publishing companies to reuse people’s tweets as the substance of an article that special tools have sprung up to help them do so. But inside these newsrooms, there is no apparent debate over whether it’s any different to embed a tweet from the President of the United States or from a vulnerable young activist who might not have anticipated her words being attached to her real identity, where she can be targeted by anonymous harassers.”

In March 2014, BuzzFeed reporter Jessica Testa published an “article” comprised mainly of tweets she’d curated from a Twitter discussion that user Steenfox kicked off about sexual assault.

That article, and subsequent outrage became part of a larger debate surrounding the way journalists use tweets. According to Steenfox, Testa had not gotten her permission to use her face or her image in the story.

A subject as touchy as the one Steenfox and her followers were discussing requires a lot of care in reporting. The people sharing their stories were survivors of sexual assault, and deserved to have both their identities and their dignities protected.

Openly publishing the names and faces of those participating in the discussion for an article clearly meant to garner links for BuzzFeed was completely irresponsible, and opened them up for further attacks and harassment, as Steenfox said she experienced herself.

Her photo went viral, finding its way onto the Facebook feed of her younger brother.

“He says, ‘you’re all over BuzzFeed’,” Steenfox said. “He was startled.”

She later battled with BuzzFeed to remove her photo from their site.

Of Testa, Steenfox said, “For all she knows, my abuser could have found me. What if I was trying to hide from that person?”

Steenfox, and many others whose tweets were included in the story, felt exposed. It’s one thing to send out a tweet to an audience of a couple hundred people. Fox has a very large following, but her 17,000 followers in no way matches the reach of a site with millions of viewers per day.

Exposing a story to that size of an audience, especially one that may not necessarily had been granted to BuzzFeed, is dangerous and irresponsible journalism.

Steenfox was harassed and trolled when the story of her dust up with BuzzFeed made it on the Poynter Institute’s site, via an article penned by resident journalism ethics expert Kelly McBride.

For her part, McBride based her opinionated article on a false premise. She misunderstood why Steenfox was angry, and used as a source one of Steenfox’s tweets in which Fox was addressing Testa for not having gotten her permission.

The entire thing turned into a nightmare for Steenfox, who had people in her mentions accusing her of wanting ownership of public tweets and being upset that her “Twitter moment was gone.”

All Steenfox wanted was her privacy to be respected. At the time, she maintained a public Twitter account with over 10,000 followers. And though she understood what she was doing when she posited the question to her audience, she never intended for that audience to grow hundreds of times over in the span of one night.

The idea that tweets are public and therefore open to be seen by everyone is an argument that is used all the time in these situations, but that argument lacks nuance.

What many of these journalists fail to grasp is that a person tweeting to a small audience may very well understand that the public tweets are subject to being shared and seen by a larger audience, but the type of exposure that comes when a larger media outlet shares your story in no way compares to 100 people on your timeline retweeting your tweet.

Consider the example of the infamous Zola, who took to Twitter to share a cautionary tale of hookers, strippers, pimps, mayhem, and murder.

After the story was retweeted hundreds of times, Zola deleted the tweets from her account, but not before they had been captured via screenshots and saved to various Imgur accounts.

When larger media outlets picked up the story, nearly none bothered to attempt to track down Zola or verify the facts of the story. Most simply provided cheeky, borderline insulting writeups, linking to screenshots others had posted.

Only WaPo’s Caitlin Dewey sought the facts behind the tale. She tracked down the parties involved, even finding others who had been in similar situations with Jess and ‘Z’, the latter turning out to be a real-life pimp currently facing charges of human trafficking, among other things.

Zola has become something of a cult hero, with movie directors contacting her about a possible dramatization of her story.

Others who have had their tweets shared on large media outlets without their knowledge have not been so lucky. Many have suffered harassment, ridicule, and in some cases, unemployment. These are things they didn’t sign up for.

The Society of Professional Journalists addresses the need for journalists to exhibit compassion in its code of ethics under the heading Minimize Harm:

What Wemple, Testa, and other journalists have done defies the ethical code. They have chosen to hide behind the idea that posting it in a public forum makes it fair game.

The time for a new code of ethics in journalism is now. In the age of new media, with so many reporters opting to do their research on the Twitter and Facebook feeds of private citizens instead of going out and doing the digging on their own, new rules must be set in place to train journalists how to handle situations like these when they arise.

(Part Two will take a closer look at the consequences of having a tweet go viral, and what happens when it nearly costs you your job.)

I don’t think there is a problem with “doing research” on Facebook and Twitter – that, to me, doesn’t seem any different than any other kind of research one might employ and I don’t think it’s fair to assume that journalists who use social media for research are somehow lazier or less skilled than journalists who don’t. But there is a difference between “doing research” and using a private citizen as a source for a story without their knowledge or permission.

Having been directed here by a Twitter link that was retweeted by a friend who was retweeting another friend of her’s, I have to say that I don’t agree with this article. Twitter has two ways to take part. Your account can be locked, in which case your tweets are hidden from public view and cannot be shared by your friends (unless they screenshot them), or your account can be open in which case anyone can read and share them. The user has the choice which to choose. I would strongly agree that if your account is locked then those who are your friends should take this as meaning they are not to share what they read there. But if your account is open then you yourself are leaving yourself open to whoever wants to read what you say. This may be be Mr Nobody with one follower. But it may be Mr Journalist who puts it in his newspaper. I would expect an ethical journalist to give those whose tweets he is using a heads up and may be even a right of reply. But I also think that if you publish “in public” (i.e. not with a locked account) then you have little expectation of privacy. Indeed, you haven’t even taken all the steps you could to make your own account private. If and when you have taken those steps then you may feel aggrieved if they are subverted.